Epilepsy is a neurological disorder caused by temporary disruptions in brain activity. It manifests through recurrent seizures, which may take various forms — from convulsions and loss of consciousness to brief changes in sensation, behavior, or perception.

Epilepsy affects people differently. Seizures can be frequent or rare, mild or severe, but thanks to modern medicine, the condition is largely manageable with proper treatment and ongoing monitoring.

It is essential to understand that epilepsy does not limit a child’s intellectual abilities or their potential to live a full life. With quality medical care, professional awareness, and psychological support, many children with epilepsy can learn, grow, play, and achieve success just like their peers.

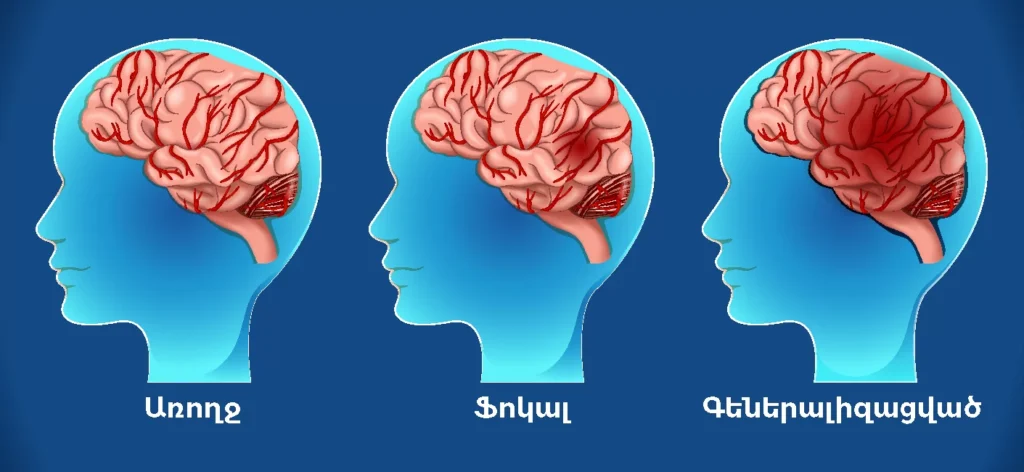

Types of Epilepsy

Based on how abnormal electrical activity begins and spreads in the brain, seizures are generally classified as:

Focal (partial) seizures

Generalized seizures

Seizures of unknown origin

Focal Seizures

These occur when excessive electrical activity is limited to a specific part of the brain.

Two main types of focal seizures:

Focal seizures without loss of consciousness

Consciousness is preserved.

May involve emotional changes or altered sensations (sight, smell, taste, hearing).

Can cause involuntary movements in one part of the body (e.g., hand or leg), or sensations like tingling, dizziness, or flashing lights.

Focal seizures with impaired awareness

Consciousness is altered or impaired.

The person may appear disconnected from their surroundings.

Often involves repetitive behaviors such as lip-smacking, hand rubbing, chewing, or swallowing motions.

Understanding focal seizure symptoms requires careful clinical observation.

Generalized Seizures

These seizures involve both sides of the brain from the outset. Six major types:

Absence seizures (Petit mal)

Common in children.

Brief loss of awareness for a few seconds, often with a fixed stare.

Eyelid fluttering and slight eye rolling may occur.

The child usually resumes activity immediately with no memory of the event.

Tonic seizures

Muscle stiffening, often affecting the back, arms, and legs.

May cause sudden falls and injuries.

Atonic seizures (Drop attacks)

Sudden loss of muscle tone, leading to unexpected collapse.

Also known as “drop seizures.”

Clonic seizures

Rhythmic, repeated jerking movements affecting the neck, face, or arms.

Myoclonic seizures

Sudden, brief muscle jerks, typically in the arms or legs.

Tonic-clonic seizures (Grand mal)

The most dramatic form.

Begins with body stiffening (tonic phase), followed by rhythmic jerking (clonic phase).

May involve a loud cry, tongue biting, or loss of bladder control.

Full recovery can take 10–30 minutes after the seizure ends.

Symptoms of Epileptic Seizures

Epileptic seizures result from excessive electrical activity in the brain’s neurons. Seizures can affect any function controlled by the brain, and symptoms may include:

Temporary confusion or disorientation

Blank stares or “frozen” expressions

Involuntary movements of the arms and legs (convulsions)

Impaired or lost consciousness

Psychological symptoms like:

Déjà vu

Distorted time perception

Dream-like states

Emotional disturbances like fear, anger, anxiety

Hallucinations or delusions

Symptoms vary depending on the seizure type. In most cases, individuals tend to experience the same type of seizure repeatedly, leading to consistent symptoms during each episode.

Diagnostic Methods for Epilepsy

Diagnosis is mainly based on clinical evaluation during a seizure and identifying underlying causes.

Common diagnostic tools include:

EEG (Electroencephalogram) – Detects abnormal electrical activity in the brain.

CT (Computed Tomography) and MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) – Help identify structural changes in the brain.

Although clinicians look for specific markers of epileptic syndromes, these are not always visible. In complex cases, video EEG monitoring can be a helpful tool.

There are specific diagnostic criteria for confirming an epilepsy diagnosis.

To confirm the diagnosis and determine the type of epilepsy, the specialist typically prescribes long-term video EEG monitoring, often including sleep recording.

Diagnosing Epilepsy

The physician determines the duration of monitoring individually, depending on the specific case, the suspected seizure type, and the purpose of the assessment.

Sometimes, a patient presents with “classic” epileptic seizure symptoms and may even provide video recordings of their episodes. Yet, the long-term EEG monitoring may not detect any epileptic activity.

In some cases, the study may need to last up to four or five days, especially when it is crucial to accurately locate the origin of the seizure activity—for example, prior to neurosurgical intervention, when it is necessary to identify the epileptogenic focus.

All EEG recordings are carefully analyzed by an epileptologist, following a thorough consultation for each patient.

Modern pharmacology has advanced to the point where the side effects of medications have been minimized almost to zero. Physicians carefully select the appropriate drug by considering factors such as the patient’s sex, age, accompanying medical conditions, and other relevant aspects. For example, during pregnancy, medications that could negatively affect the fetus are avoided.

Long-term safety of antiepileptic drugs:

When prescribing therapy, doctors always weigh the benefits against the risks, ensuring that the benefits clearly outweigh any potential harm. The treatment must be effective.

For instance, if a patient’s seizures have completely stopped while on a medication but they experience numerous side effects and poorly tolerate the therapy, this is an indication to switch medications despite its effectiveness.

The same antiepileptic drug can have different levels of effectiveness in different patients with the same type of epilepsy.

Therefore, the doctor always inquires about:

The frequency of seizures,

The patient’s tolerance to therapy,

The overall well-being,

and based on these factors decides whether to continue with the current medication, reduce, or increase the dosage.

It is estimated that up to 25% of epilepsy cases are potentially preventable. The most effective way to prevent post-traumatic epilepsy is to avoid head injuries, particularly by reducing the risk of falls, traffic accidents, and sports-related injuries.

![]() For children, it is important to:

For children, it is important to:

![]() Strictly follow a daily routine,

Strictly follow a daily routine,

![]() Avoid disrupting nighttime sleep,

Avoid disrupting nighttime sleep,

![]() Choose a proper, balanced diet,

Choose a proper, balanced diet,

![]() Protect against head injuries,

Protect against head injuries,

![]() Timely treat any illnesses, especially infectious diseases.

Timely treat any illnesses, especially infectious diseases.